Whether you’re in EdTech or a nonprofit leader, chances are you’ve struggled to get a solid “yes” on your data request.

You decide to do evidence the serious way by getting a real education program evaluation that can hold up in a superintendent’s office, a school board meeting, or a grant review panel.

You draft a scope, discuss outcomes, and bring in a consultant. You start picturing the final deck. Then you hit a roadblock: you need student-outcome data.

Not usage data. Not logins. Not minutes. Outcomes districts actually use for data-driven decision making in education: assessment performance, attendance rate, behavioral referrals, suspensions, and course grades.

So, you send the data request. And the district says no. Or stays silent. Or replies weeks later with a polite version of “not at this time.”

That’s the real failure mode of education program evaluation. It’s rarely the analysis, but the access. It’s the quiet reality that you can spend real money on education evaluation consulting and still end up with no district partner or usable data.

The fastest way to derail an independent EdTech impact evaluation is to make the district feel like they’re signing up for more work.

Districts don’t reject requests because they hate evaluation. They reject requests because their teams are overloaded, privacy is high-stakes, and vague requests look like long projects with unknown lift.

If you want a “yes,” your request has to feel safe, aligned, and low-burden while still supporting rigorous education impact evaluation methods. If you follow the steps in this playbook, you’ll increase your odds of getting the data and the “yes” you need.

The Problem Nobody Budgets For: District “No”

A rigorous impact evaluation in K–12 usually needs a credible comparison group.

If you serve students and their scores rise, you have a story. But you don’t have an answer. Scores rise for lots of reasons: maturation, teacher practices, other supports, attendance improvements, and professional development.

A credible evaluation asks: Did outcomes improve more than we would expect, compared to similar students who did not receive the program during the same window?

That’s why rapid-cycle evaluation often relies on between-groups designs and matching instead of pretending the counterfactual is “nothing.” The cleanest, lowest-burden way to build a counterfactual is often district administrative data. That means the entire evaluation depends on the district agreeing to share data.

And when the district declines, the cost still lands. Planning happened. Documents were drafted. Meetings took place. Time was spent. That’s why a “district no” is expensive. Not emotionally, but financially.

You can’t control district capacity, but you can control how your request lands.

What Districts Are Really Saying “No” To

Most rejections are due to capacity and risk management. The district is protecting staff time and protecting students.

Time and Staff Constraints

District data teams have competing priorities: accountability reporting, internal dashboards, state compliance, enrollment forecasting, attendance audits, discipline reporting, board requests, and grant reporting.

When you ask for data, you’re not asking for “a file.” You’re asking for hours: interpretation, mapping fields, writing queries, extracting records, scrubbing identifiers, secure transfer, and documentation. If your request is unclear, the first few hours go to deciphering what you mean.

Compliance, Privacy, and Risk

Data requests trigger FERPA concerns, security review, governance processes, and reputational anxiety. Districts can’t assume you’re safe. They have to see it in your documentation.

Vague Requests Look Expensive

“All your test data for 2022” signals you don’t understand their systems. It signals back-and-forth. It signals scope creep. When districts can’t estimate effort, they default to “no.”

Misalignment With Priorities

Districts prioritize requests tied to strategic priorities: literacy, attendance, behavior, equity goals, curriculum adoption, renewals, and budget scrutiny. If you frame it as “help us with our study,” you’re asking them to spend capacity on your agenda. If you frame it as “help us answer a question that supports your decision-making,” you’re speaking their language.

The 4-Step Playbook for Getting to “Yes”

A good data request is not about being persuasive, but about how you frame your request. You reduce workload, reduce perceived risk, and increase perceived value by doing four things:

- Design for secondary data, not new data collection

- Request data from the district, not individual schools

- Secure a district champion and align to priorities

- Show up with “ducks in a row” documentation

Together, these moves increase approval odds and protect rigor.

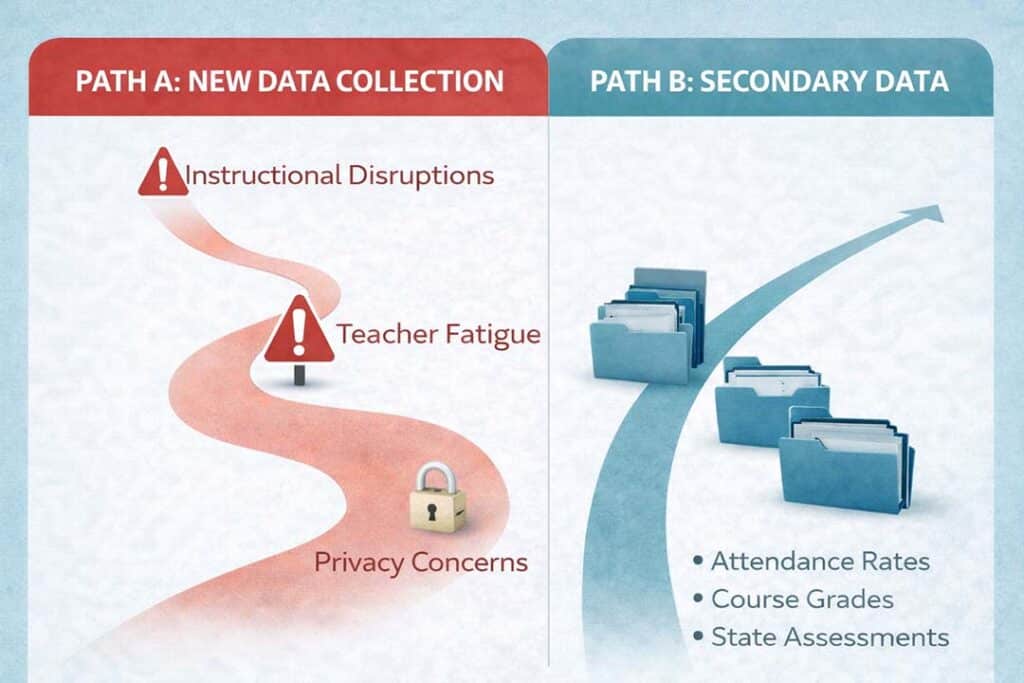

Step 1: Design For Secondary Data, Not “New Data Collection”

Secondary data is straightforward: data already collected for district operations.

This is the foundation of low-burden program evaluation and rapid-cycle impact evaluation. You’re not asking districts to administer new surveys, run extra testing, or host researchers in classrooms. You’re using what already exists.

New data collection triggers everything districts resist: scheduling burdens, instructional disruptions, new approvals, principal skepticism, teacher fatigue, and privacy concerns. The more intrusive the design, the more your request looks like a project that will sprawl.

Secondary data can still support strong education impact evaluation methods when paired with a credible comparison strategy.

Common district-owned outcomes that often support K–12 impact evaluation services:

- district and state assessment performance

- benchmark assessments (district-dependent)

- course grades and credit accumulation

- attendance rate and chronic absenteeism indicators

- behavior referrals and discipline incidents

- suspensions and expulsions

- program participation flags and service logs

Many organizations assume the problem is “we need more data.” In reality, districts often have data bloat. The gap is in analysis and interpretation. That’s why education data analysis services and student data analysis for schools matter: turning existing data into decision-grade insight.

This step also prevents a common trap: treating usage as outcomes. EdTech usage vs. outcome data gets confused all the time. Usage helps you understand implementation, but it does not prove impact.

If your product targets Grade 3 reading growth, don’t request “assessment data.” Request the specific Grade 3 reading assessments the district already administers. That one detail often signals competence immediately.

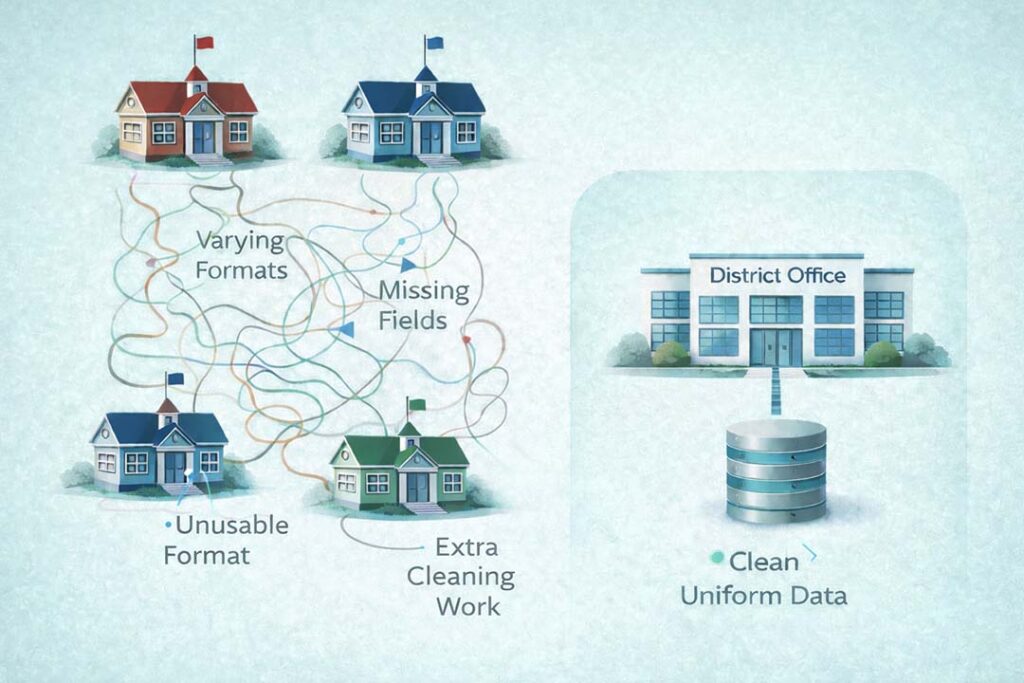

Step 2: Request Data from the District, Not Individual Schools

Even when schools want to help, they often can’t pull data in a usable format. Schools are built to educate students, not to run clean extracts from administrative systems.

When you request data school-by-school, you multiply the inconsistency:

- varying formats

- missing fields

- mismatched definitions

- uneven timelines

- higher dropout risk

You also create extra student data cleaning and preparation work you didn’t plan for, and that noise weakens the evaluation.

District-level requests reduce that risk. District administrative teams are more likely to know:

- where fields live

- assessment naming conventions and testing windows

- how to export consistently

- how to apply uniform de-identification

- how to document definitions for interpretation

District access also helps with comparison groups. A district can provide the broader “universe” from which comparable non-participants can be matched for independent K–12 program evaluation. A single school often can’t.

This matters for student outcome trends and reporting, too. Standardized, district-level extracts produce fewer caveats and fewer “we can’t interpret this because the file changed across sites” issues.

If your goal is fast program evaluation services and repeatable rapid-cycle evaluation, district-level extraction is the clearest pathway.

Step 3: Secure a District Champion and Align to Priorities

If you want your request prioritized, you need someone inside the district who cares about the answer. Not someone who likes you. Someone who benefits from clarity.

The best champions are often director-level leaders (or higher) tied to outcomes: Curriculum and Instruction, Student Support, MTSS, Attendance, Behavior, or a district initiative owner.

Their job is not pulling the data. It’s actually helping your request become a priority by connecting it to district needs:

- evidence-based decision making in schools

- risk reduction in renewals and procurement

- budget justification

- education program ROI measurement

District leaders have to constantly defend their decisions. Third-party education evaluation helps them answer the uncomfortable questions:

- Why did we adopt this?

- Why renew it?

- What changed for students?

- What happens if we cut it?

A champion-forward framing should be short and forwardable:

We’re estimating the impact of [program/product] on student outcomes using existing district data, with minimal lift for staff. We’ll focus on [2–3 priority outcomes] during [study window]. Data will be securely transferred, used only for this analysis, and destroyed per agreement. The output will be a clear summary that leaders can use for planning and budgeting.

That language signals partnership and an evaluation culture mindset, not a data grab.

Step 4: Show Up With “Ducks in a Row” Documentation

This is the step that most directly increases approval odds. Districts have external research request processes for a reason. What they need is governance, clarity, and consistent standards for data sharing.

You don’t win by fighting the process. You win by making it easy for them to say yes.

Follow The District’s External Research Request Process

Expect forms and review. Sometimes an IRB-ish process. Expect a security lens. When you show impatience, you become a risk. When you demonstrate competence, you become a partner and earn their approval.

This is one of the cleanest signals of program evaluation best practices and of how to choose a program evaluation consultant: good evaluators can navigate district workflows without creating chaos.

Be Specific About Data Fields and Structure

Spell out:

- study purpose and study window

- requested outcomes

- roster definition (who received the program, when, how identified)

- high-level matching variables

- data security plan

- destruction timeline

- point of contact

Education data interpretation starts here. If you can’t define what you need, you can’t interpret what you receive.

Provide Two Files That Reduce Back-And-Forth

The gold standard is not a long email. It’s two attachments.

- Excel mockup with fake data: Column names, example values, and the intended structure. One row per student per assessment, or whatever the record rule is.

- Data dictionary (Word document): Defines each field, allowed values, formatting rules, and record rules. For example: one record for each assessment administered between 2022-09-01 and 2023-12-31.

This is upfront student data cleaning and preparation. It reduces the work districts fear and the errors that bleed into study results.

Demonstrate You Understand District Data Reality

District staff can tell quickly whether you understand their world. “All assessments” sounds like an outsider. “Grade 3 reading benchmark, fall and spring windows” sounds like someone who did their homework.

Ask before you request:

- Which assessments does the district administer for this grade band?

- What are the testing windows?

- Are there multiple forms or scales?

- How are course grades structured?

- How are behavior incidents coded?

Competence lowers perceived lift, and a lower lift raises approval odds.

What A “Yes-Ready” Data Request Includes

A strong request reads like it was designed to save district time:

- research question tied to district priorities

- 2–3 outcomes, defined specifically

- study timeframe

- roster definition

- minimal burden statement

- privacy/security plan + destruction timeline

- Excel mockup

- data dictionary

- point of contact

- champion support or internal alignment

That’s what program evaluation services look like when they’re built for real-world constraints. It’s also why knowing where to find a “K–12 evaluation consultant near me” is less important than “can this evaluator make the process easy to approve and easy to repeat.”

The Real Win Is Repeatable Evaluation

If the evaluation process is so heavy that you’ll never do it again, it isn’t serving districts, vendors, or students. One-off studies create narrative moments, yet they don’t create learning systems.

Rapid-cycle evaluation is a strategy because it respects reality: decisions happen on timelines. Renewals come. Budgets shift. Implementation changes. Leaders need answers while school is still happening.

This playbook is about designing requests that meet districts where they are: overloaded, careful, and still committed to improving outcomes. If you do that, you’ll receive more positive responses than negative ones.

Reduce burden. Increase clarity. Align to priorities. That’s how a “no” response becomes “yes, we can do that for you.”