By the time the renewal conversation happens, the decision is rarely theoretical.

A Director of Curriculum has a vendor deck open on one screen and a district outcomes dashboard on the other. The vendor slides are crisp: implementation milestones, usage growth, success stories, a quote or two that sounds ready for a conference stage.

The district data is messier. Benchmark scores vary by school. Attendance patterns wobble. Subgroup trends don’t move in sync. Someone points out that one campus looks like a different district entirely.

Then the question: “How do we actually know this program made a difference?”

Not “Did teachers like it?” Not “Did we roll it out?” Not “Did students log in?”

Did it move student outcomes enough to justify keeping it, expanding it, or replacing it?

That’s where the usual evidence starts to feel thin. Usage is not impact. Testimonials can be sincere and still be incomplete. And randomized controlled trials, while valuable, rarely show up on a timeline that matches a district’s budget cycle or procurement calendar.

This is the moment where real education program evaluation lives: in the gap between what leaders want to know and what traditional research timelines can realistically deliver.Quasi-experimental designs exist for that gap. They help districts, EdTech companies, and educational nonprofits move from hopeful stories to defensible decisions using the data schools already have.

Why Causal Questions Are Hard in K–12

A lot of education data tells you what happened. Much less of it tells you why it happened.

Descriptive data can show trends: scores rose, attendance improved, discipline incidents dropped. Causal inference asks something sharper: what changed because of the program, service, or intervention?

In K–12, clean causal answers are hard for reasons that are more human than methodological:

- Ethics: districts may not be willing to deny students access to a potentially helpful program just to create a perfect comparison.

- Operations: schedules shift, staffing changes, testing windows disrupt instruction, and mid-year launches collide with reality.

- Timing: leaders often need answers inside a decision window that doesn’t allow multi-year studies.

- Mobility: students move in and out of schools and programs, and the data trail isn’t always complete.

- Implementation variability: some schools run a program with strong fidelity, others do what they can with limited capacity.

That’s why the questions in program evaluation for school districts tend to sound like:

- Did this improve student outcomes?

- Would outcomes have improved anyway?

- Is it worth renewing, scaling, or cutting?

Those questions can’t be answered well with simple before-and-after comparisons, because “after” does not automatically mean “because.” Outcomes change for plenty of reasons: maturation, regression to the mean, district-wide shifts, staff changes, or shifts in who is enrolled.

Strong education impact evaluation methods don’t require schools to become laboratories. They require evaluation designs built for the environment schools actually operate in.

What Is a Quasi-Experimental Design?

A quasi-experimental design estimates program impact by comparing outcomes between groups when random assignment isn’t possible.

The key phrase is designed comparison.

A quasi-experimental study is not “let’s compare School A to School B and call it impact.” Done well, it’s a structured attempt to answer a causal question using real constraints and real data.

It’s also useful to name what it isn’t:

- not anecdotal evidence

- not a correlation dressed up as rigor

- not a trend line that assumes the program caused whatever happened next

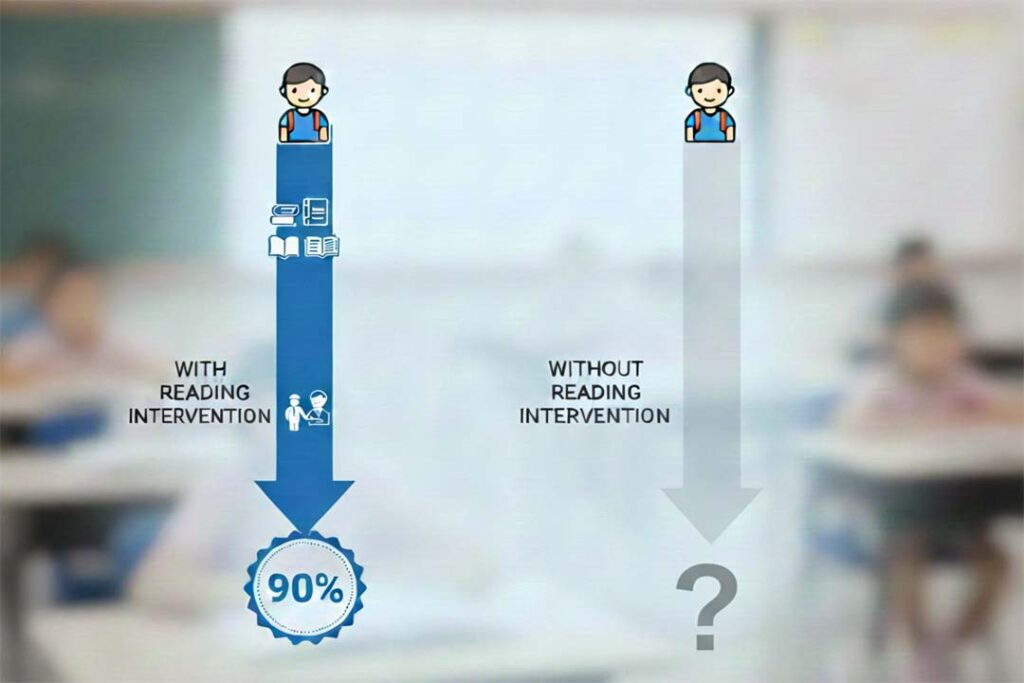

At the center of quasi-experimental evaluation is one concept: a credible counterfactual.

In plain language: if students received an intervention, what would their outcomes have looked like if they had not?

Random assignment makes counterfactuals easier. In most K–12 contexts, randomization isn’t available. Quasi-experimental designs create a stand-in for the counterfactual using comparison groups, pre-program data, and careful design choices.

That’s why quasi-experimental methods are often the workhorse of independent evaluations in real districts. They allow education program evaluation to be both rigorous and usable.

Quasi-Experimental Designs vs. Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials have earned their reputation. For early research and controlled pilots, they can provide strong evidence about whether something can work under ideal conditions.

But “ideal conditions” is rarely the question that drives district-wide decisions.

RCTs can be hard to align with district realities because they often involve cost, long timelines, specialized infrastructure, and implementation conditions that don’t match scaled rollouts.

A practical framing is this:

- RCTs ask: Can this work under ideal conditions?

- Quasi-experimental designs ask: Did this work here, under real conditions?

That second question tends to be the dominant one for large districts, and it’s central to EdTech impact evaluation and nonprofit impact reporting. Leaders want evidence that reflects actual adoption patterns, attendance variation, and real implementation friction, not a perfect pilot environment.

Quasi-experimental approaches are attractive because they often deliver faster, lower-burden, more context-relevant evidence that fits decision cycles.

Common Quasi-Experimental Designs Used in K–12

Quasi-experimental design is a category, not one method. In practice, K–12 evaluation often relies on a few core approaches.

Between-Groups Pre-Post Designs

This approach compares changes over time between:

- students who received the program (treatment group)

- similar students who did not (comparison group)

The credibility of the results hinges on baseline equivalence. If the groups were already meaningfully different before the program started, post-program differences may reflect those pre-existing gaps rather than impact.

That’s why good evaluation doesn’t stop at “we found a comparison group.” It asks whether the groups are comparable and what adjustments are needed.

Matched Comparison Designs

Matching takes “similar students” seriously. Instead of choosing a comparison group based on convenience, matching uses existing student data to identify non-participating students who resemble participating students on relevant characteristics (prior achievement, attendance history, demographics, program history, school context).

This is where propensity score matching often appears. Rather than matching on a single variable, propensity scores estimate the likelihood a student would be in the program based on observed characteristics. Students with similar likelihoods are matched across groups, strengthening the counterfactual.

Matching doesn’t make the evaluation perfect, but it often makes it meaningfully more credible.

Difference-in-Differences Logic

Difference-in-differences focuses on relative change, not just where groups end up.

The question becomes: did the treatment group improve more (or decline less) than the comparison group over the same period?

That logic can reduce bias from external factors affecting both groups, like district-wide policy shifts, schedule disruptions, or broad curriculum changes. It doesn’t pretend the world stood still. It estimates impact inside the same messy world both groups experienced.

What Strong Quasi-Experimental Designs Share

Across methods, strong quasi-experimental evaluations tend to share the same fundamentals:

- clear definitions of treatment and comparison groups

- outcomes chosen for decision relevance, not convenience

- transparent assumptions

- careful attention to baseline differences

- interpretation that stays honest about what the design supports

Why Matching Matters More Than Most People Realize

If quasi-experimental evaluation has a quiet villain, it’s the bad comparison.

The biggest risk is not that a method sounds technical. It’s that the comparison group is not actually comparable.

Two common traps show up constantly:

- Motivated schools vs. struggling schools: schools that opt into something new may differ in leadership stability, teacher buy-in, staffing, or culture.

- Opt-in users vs. non-users: students who engage consistently often differ from those who don’t in attendance patterns, support systems, or prior achievement.

If an evaluation compares “high users” to “non-users,” it often inflates impact because selection bias is baked into the comparison.

Propensity score matching helps by shifting the question away from “who used it” and toward “who was similar before it started.” It uses the data you already have to build a fairer comparison. It can’t control every unobserved factor, but it strengthens credibility in a way that matters when findings will be discussed with boards, funders, or procurement stakeholders.

Quasi-Experimental Designs in Rapid-Cycle Evaluation

One of the most common objections to rigorous evaluation is speed.

Districts don’t have years. Renewal and budget cycles force decisions now. EdTech companies need evidence that fits sales and retention cycles. Nonprofits need impact results that align with grant and donor timelines.

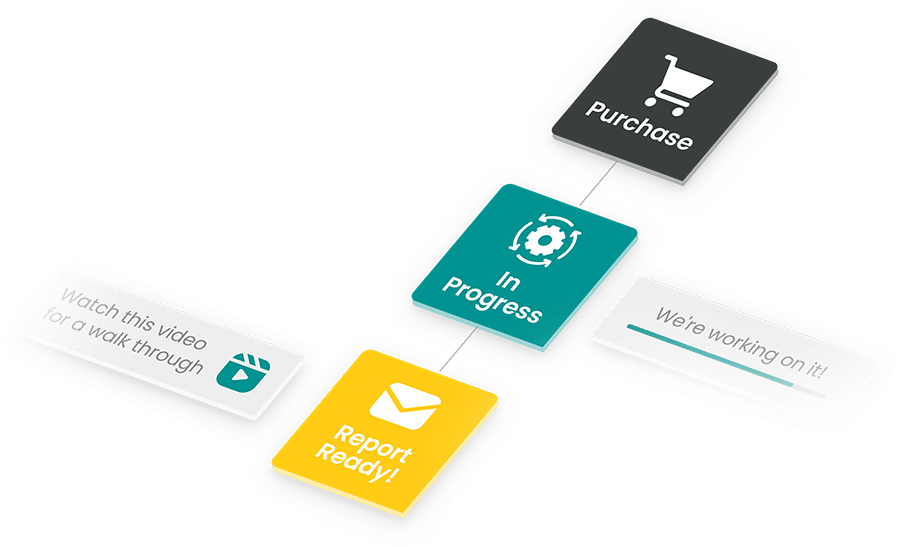

This is where rapid-cycle evaluation becomes essential.

Rapid-cycle evaluation is not “fast because we cut corners.” It’s fast because it relies on designs that can use:

- existing district data

- retrospective analysis

- predefined outcomes already collected

Quasi-experimental methods often power rapid-cycle work because they can estimate impact without building an entirely new data collection system.

This is also where MomentMN Snapshot Reports fit naturally. Snapshot Reports use a quasi-experimental, between-groups pre- and post-test design with multivariate matching via propensity scores, built to deliver clear, defensible impact estimates with minimal burden on district staff.

The goal is to provide evidence they can trust and explain inside real decision windows.

How Different Audiences Use These Results

Quasi-experimental evidence matters because it supports action.

District leaders use it to make renewal and scaling decisions, justify spending, answer board questions, and evaluate equity across subgroups. It helps replace “we think it’s working” with something more defensible.

EdTech leaders use independent impact evidence to build credibility, strengthen sales narratives, support retention, and learn where impact is strongest (or where implementation support may need to improve). This is the backbone of strong EdTech impact evaluation because it moves messaging beyond adoption metrics.

Educational nonprofits use quasi-experimental evidence for grant reporting, donor confidence, annual impact reporting, and stronger district partnerships. It helps prove impact without requiring unrealistic perfection in implementation.

Common Misconceptions About Quasi-Experimental Designs

Three misconceptions often surface but don’t accurately reflect what quasi-experimental designs can offer in the educational sector.

- “It’s not rigorous.” It can be rigorous. The real question is whether the design creates a credible comparison, makes assumptions explicit, and measures outcomes in a decision-relevant way.

- “It’s just correlation.” Bad comparisons rely on correlation. Well designed comparisons can support causal inference. Quasi-experimental evaluation is specifically about building a stronger counterfactual than convenience comparisons.

- “Implementation issues make results meaningless.” Implementation issues make results realistic. Leaders need to know impact under real conditions, not fantasy conditions. If a program “works” only with perfect usage and perfect scheduling, that’s important information too.

Once you’re aware of these common misunderstandings, you’ll not only understand the power of quasi-experimental methodologies, but you’ll also know what strong evidence should look like, and what isn’t strong enough to hold up in a meeting room with stakeholders.

What Strong Quasi-Experimental Evidence Looks Like

Strong quasi-experimental evidence tends to be recognizable even to non-technical readers. It usually includes:

- a transparent explanation of group definitions and matching

- outcomes that matter for decisions (achievement, attendance, behavior, course performance)

- honest limitations and clear boundaries on claims

- interpretation that connects results to next steps: renew, scale, adjust, target, or stop

That’s what supports a healthier evaluation culture: using evidence to learn and make better decisions, not simply defend past choices. In K–12 settings, this often means looking at outcomes districts already track, like benchmark or district assessments, attendance/chronic absenteeism, and behavior referrals or suspensions.

From Theory to Confident Decisions

Quasi-experimental designs aren’t a consolation prize for districts that can’t run randomized trials. They are often the right tool for real-world K–12 decision-making.

They acknowledge constraints without giving up rigor. They work with timelines that match actual budget and renewal cycles. They help districts, EdTech companies, and nonprofits move beyond dashboards and anecdotes to a clearer view of what is truly improving outcomes for students.

If you’re responsible for a major K–12 investment, you don’t need perfect evidence. You need credible evidence that reflects your students and your context. Quasi-experimental evaluation exists to provide that.