The product looks like it’s working. Usage is strong. Teachers are logging in. Students are engaging. The anecdotes are plentiful and sincere. A principal shares a story about a student who finally turned a corner. A district leader mentions fewer complaints this year. A nonprofit sees early indicators moving in the right direction.

Then comes the inevitable request. Someone asks for “real proof.”

That’s when the phrase randomized controlled trial, or RCT, enters the conversation, and the temperature changes.

RCTs carry that kind of weight for a reason. An RCT assigns students (or schools) to receive the program or not by random chance, then compares outcomes later. They’re widely treated as the strongest tool for causal inference.

Federal evidence frameworks reinforce that posture, and the education field has built an entire credibility ladder around designs that meet those standards. The What Works Clearinghouse handbooks lay out that ladder in explicit terms: what qualifies as strong evidence, what falls short, and why.

But RCTs test programs and assumptions behind them. And in education program evaluation, those assumptions are often where the disappointment starts.

Why RCTs Feel So Reassuring (Before You Run One)

The appeal of an RCT is easy to understand, especially in K–12 environments where leaders are under constant pressure to justify decisions.

Random assignment feels fair. If students are assigned to treatment and control groups by chance, no one can argue that the deck was stacked. Causality feels clean. If outcomes differ, the program gets the credit. If they don’t, it doesn’t. Reviewers, boards, and funders recognize the term instantly. You don’t need a methods lesson just to explain why the results matter.

RCTs also carry institutional legitimacy. The WWC standards are not casual about what “meets standards.” They’re structured precisely to protect decision-makers from being persuaded by weak evidence dressed up as strong claims.

And when conditions are right, randomized controlled trial education research can do exactly what people hope it will do: isolate a program’s average causal effect under specified conditions. The design is powerful.

The Part No One Emphasizes Enough: RCTs Are Designed to Be Hard to Win

This is the emotional pivot point of the conversation, and it’s where expectations quietly collide with design reality.

In real districts, control students are rarely unsupported. Schools do not withhold help from struggling students simply because a study is running. If a literacy tool is being tested, students not receiving it are almost certainly receiving something else intended to address the same need. Tiered supports keep functioning. Intervention systems keep functioning. Instruction doesn’t pause.

That’s the system doing its job. And it changes how results should be read.

An RCT is designed to control for selection bias. That’s the selling point. The students who get the program are not supposed to be the students who were already more motivated, more supported at home, or more likely to improve for reasons unrelated to the program. Those advantages are intentionally flattened.

So the RCT removes the hidden tailwinds that often make programs look effective in observational data.

What’s left is a much narrower question: Does this program outperform everything else students are receiving by enough to detect a statistically significant difference?

That is a very high bar.

It’s also a bar that many education products and services were never built to clear, at least not on the first attempt, in a single year, under real implementation conditions. Not because they’re useless, but because the counterfactual in education is rarely “nothing.” The counterfactual is usually “another set of supports that also moves the needle.”

This is why effect sizes shrink fast under randomization. The comparison is no longer “before versus after.” It’s not “participants versus nonparticipants.” It’s participants versus other supported students moving through the same district context at the same time.

This is not a failure of randomization. It is the entire point of it. And it’s why an RCT can be an expensive way to discover that your strongest evidence story was not as strong as it could have been.

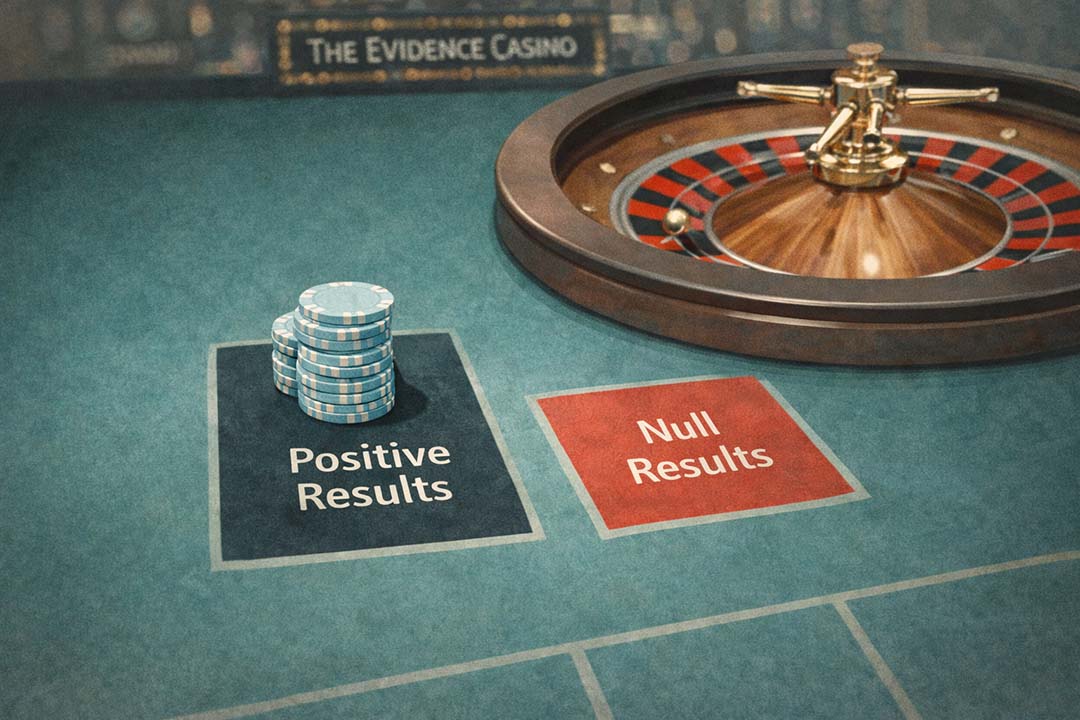

Why “No Significant Impact” Is the Most Common Outcome

When organizations receive RCT results showing no statistically significant difference, the reaction is often emotional.

Disappointment. Confusion. Sometimes defensiveness. Occasionally denial.

But null or modest findings are common in well-designed randomized trials, especially when several conditions are present:

- The outcome window is short

- The intervention is one of many supports

- The program is still evolving

- Implementation is uneven

- The outcome measure is not tightly matched to what the program actually changes

That’s not what an EdTech team wants to show decision makers.

A non-significant result does not mean “this doesn’t work.” It means “this did not outperform everything else happening at the same time by enough to detect with this sample, within this timeframe.”

Methodologists have been saying for decades that RCTs are valuable tools, but they do not automatically produce sturdy, portable truth. Deaton and Cartwright are blunt about the cultural overconfidence people attach to RCTs, especially the assumption that randomization alone makes results impregnable or universally generalizable.

Even outside education, literature describing RCT limitations consistently points to the same friction: RCTs are expensive, slow, and often answer a narrower question than decision-makers think they’re asking.

So when an RCT comes back with “no significant difference,” that result can be technically correct and still emotionally shocking, because it collides with what people thought they were buying:

- They thought they were buying validation.

- They bought a design built to remove flattering bias.

That’s the difference between “we measured something rigorously” and “we got the story we hoped for.”

The Real Cost Isn’t Just Money

RCTs are expensive in dollars, but that’s rarely the most important cost.

They require time. Coordination. Compliance. Data agreements. Monitoring. Patience. Often, they require a level of operational discipline that is simply not how districts or vendors naturally function day to day.

And because the investment is so heavy, most organizations run one RCT and then stop. Not because they no longer care about evidence, but because the process is too difficult to repeat regularly.

This creates a quiet but consequential problem.

If you won’t run another study for three years, how do you know whether changes you make next semester are helping or hurting? How do you evaluate product updates, implementation tweaks, staffing shifts, or policy changes that happen after the trial ends?

This is where the emotional sting really lands, because it’s final in a system that needs feedback.

Education leaders don’t just need evidence of effectiveness. They need evidence that keeps pace with decision cycles: renewals, budgets, staffing, and program changes.

An RCT often can’t do that. And that’s brutal if you need a renewal decision in May.

Why RCTs Are a Poor Fit for Early or Iterative Decisions

This is where many education organizations quietly misalign method and question.

RCTs struggle when:

- Products are still changing

- Implementation is uneven across sites

- Leaders need directional insight rather than a verdict

- The question is “how do we improve?” not “is this proven?”

Education systems don’t move in clean, frozen conditions. They move while teaching, hiring, adjusting schedules, responding to families, and supporting students in real time.

RCTs are best for confirmation. They answer questions like: Is this stable, mature intervention ready for scale?

Most organizations, most of the time, are asking a different question: Are we moving in the right direction, and for whom?

Those questions require navigation, not judgment.

This is one reason industry commentary has become more skeptical of the automatic “gold standard” reflex in edtech evidence of effectiveness. It’s pushing back on the idea that an RCT label should end the conversation instead of starting deeper questions about fit, design quality, and decision usefulness.

What Rapid-Cycle Impact Evaluation Does Differently

Rapid-cycle evaluation starts from a different premise.

Instead of asking the world to stand still, it works with the data systems and constraints that already exist. It leverages existing district data. It compares similar students receiving different supports during the same period. It focuses on relative change rather than perfection.

The goal is to produce evidence that is strong enough, fast enough, and clear enough to inform real decisions. This is not a “lighter” evaluation. It is an evaluation designed for decisions, not journals.

Why the RCT Can Hurt More Than It Helps

Here’s the part people rarely plan for: an RCT does not just provide information. It creates a narrative event.

If the result is strong and positive, everyone wants to cite it. If the result is null, everyone wants to interpret it like a verdict.

And because RCTs are culturally treated as definitive, a null result can shape perception far beyond what the study actually supports.

It can:

- Stall renewal decisions, even if other indicators are positive

- Weaken a nonprofit’s grant narrative even if implementation is improving

- Become a sales liability for an edtech company, even if the product is valued and adopted

- Create organizational paralysis, because no one knows what to do next

This is where the “feelings hurt” line is not just a joke. It’s a shorthand for a real organizational experience: you spend heavily, endure the burden, wait a long time, and the answer you get is either disappointing or difficult to act on.

Then you avoid evaluation for the next few years because no one wants to repeat the pain. That cycle is not a rigor problem. It’s a strategy problem.

The Smarter Sequence: Learn First, Prove Later

There is a defensible sequence that many organizations overlook, often because evidence culture has taught them to aim for the highest bar first.

A more sustainable path looks like this:

- Use rapid, quasi-experimental studies to detect a signal. Look for consistent patterns of relative improvement. Identify where outcomes move and where they don’t. Learn which subgroups benefit most and where implementation breaks down.

- Improve implementation based on what you learn. Adjust training. Refine targeting. Clarify expectations. Let the program stabilize.

- Only then invest in an RCT if the signal is strong and stable. If you’ve already seen promising results under rigorous, practical designs, you’re less likely to spend big money just to confirm uncertainty.

This sequence does not lower standards, but reduces the odds of spending heavily just to be disappointed. Th.

It also aligns with a broader critique that has shown up in nonprofit evaluation conversations: RCTs can slow agility, consume capacity, and shift attention away from improvement. That doesn’t mean “never run them.” It means being honest about what they cost and what they crowd out.

How MomentMN Snapshot Reports Fit This Reality

This is the gap many districts and partners keep running into: they need evidence that’s rigorous enough to inform decisions, but practical enough to fit real timelines and real data environments.

A strong, rapid-cycle approach keeps what decision-makers actually like about “simple” designs:

- It leverages existing district data

- It minimizes the burden on staff

- It focuses on outcomes leaders already care about (attendance, behavior, district assessments)

- It produces results fast enough to use

But it addresses the core limitation that makes simple designs fragile: the absence of a credible counterfactual.

This is where a rigorous quasi-experimental approach changes the entire conversation. Instead of “scores went up,” the question becomes “did scores go up more than we would expect, compared to similar students who did not receive the intervention?” That’s what matching is doing: building a credible comparison from existing district data without asking schools to pause the real world.

That’s decision-grade evidence. And it supports the kind of narrative that holds up in the rooms that matter: renewal conversations, procurement discussions, grant reporting, and board-level accountability.

Choosing Rigor That Matches the Question

The most productive evaluation conversations start by listening closely to the question hiding underneath the request.

If the question is, “Are we moving in the right direction?” an RCT is probably the wrong first step.

If the question is, “Is this ready for national scale and policy-level claims?” then yes, an RCT may be exactly right.

The mistake isn’t using rigorous methods. It’s skipping the methods that help you learn before you’re ready to be judged.

Education systems are complex, adaptive environments. Evidence that supports good decisions in those systems has to respect that complexity rather than pretend it doesn’t exist.

RCTs still have a role. They just aren’t the place to start.