By the time the renewal conversation happens, the decision is rarely theoretical.

You have a vendor update deck open on one screen and a district outcomes dashboard on the other. The vendor slides are polished: implementation steps, usage growth, and a few success stories that sound ready for a conference stage. The district data is less cooperative. Benchmark scores vary by school. Attendance trends wobble. One subgroup climbs while another stays flat. Someone points out that one campus looks like a different district entirely.

Then someone asks the question everyone is thinking: “Can’t we just compare before and after?”

It’s a fair question. Pre-post designs can be useful tools, especially when the goal is to learn quickly, spot patterns, and improve implementation. They can also become a trap when they’re used to justify high-stakes decisions that require stronger evidence than a simple time comparison can provide.

Because the worst outcome isn’t imperfect evidence. It’s evidence that sounds confident, circulates widely, and then crumbles the first time someone asks a reasonable follow-up question.

What a Pre-Post Design Actually Is (and What It Isn’t)

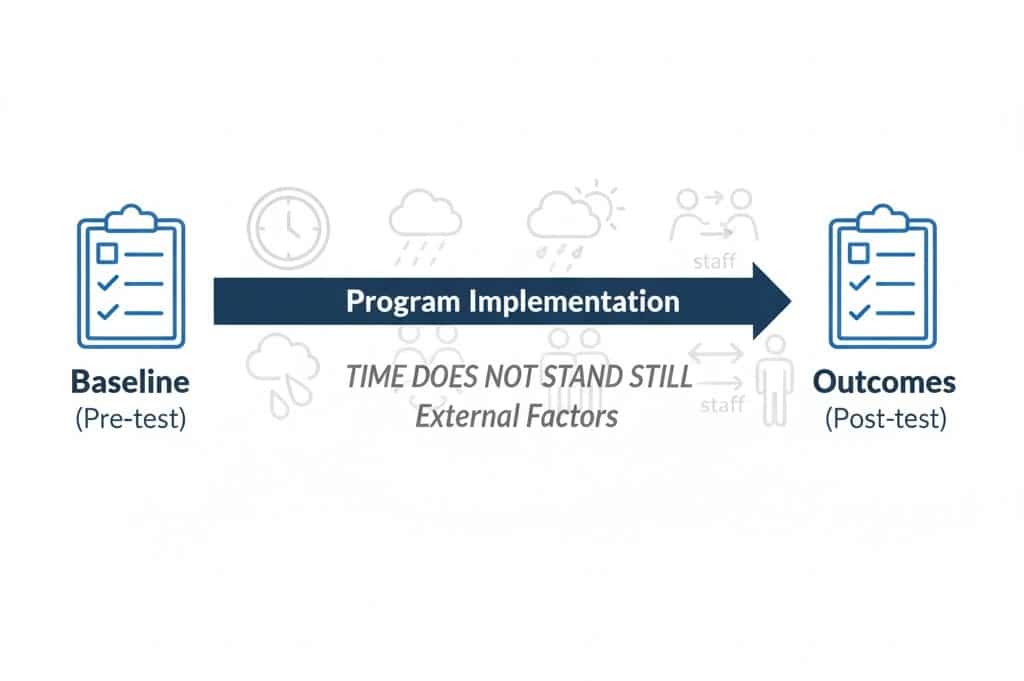

A pre-post design compares outcomes measured before a program or intervention to outcomes measured after the program.

In research language, this is often called a one-group pretest-posttest design. It’s widely discussed in methods training because it’s common and intuitive, but it’s typically categorized as pre-experimental, not causal.

That classification isn’t an insult. It’s a warning label. It’s a reminder that “change over time” is not the same thing as “impact caused by the program.”

So what can a pre-post design do well? A good pre-post analysis can:

- describe change over time within a group

- highlight patterns worth exploring further

- support formative learning and internal improvement

- give early signals about whether outcomes are moving in a promising direction

And what can’t it do on its own? It cannot reliably:

- isolate the program’s effect from everything else happening during the same period

- rule out other plausible explanations for change

- support strong causal claims

- carry the full weight of high-stakes renewal, scaling, or funding decisions

Pre-post designs answer: “What changed?”

They do not reliably answer: “What changed because of this program?”

That distinction matters more than most people expect, especially once results leave an internal dashboard and enter a board packet, a grant report, or a procurement discussion where leaders are being asked to defend decisions.

Why Pre-Post Designs Are So Common in K–12

Pre-post designs are common because they fit the reality of how K–12 systems work.

Districts already collect outcome data. Nonprofits already track program participants. EdTech platforms already log usage and performance metrics. In many cases, the only “extra” step is pulling a dataset and comparing two time points.

Pre-post also feels fair. It doesn’t require withholding services. It doesn’t ask schools to become laboratories. It doesn’t introduce complicated comparisons that require a methods lesson just to explain the results.

And it’s fast. Speed matters. District timelines are driven by budget cycles and renewal windows. Nonprofits have donor updates and grant reporting deadlines. EdTech companies operate on sales cycles and customer retention calendars that do not pause for a multi-year study.

So pre-post designs show up because they reduce friction. They help teams start asking better questions. They create a baseline from which more rigorous evaluation can grow.

The problem isn’t that pre-post designs exist. It’s that they’re often asked to answer questions they can’t answer, especially when the stakes are high and the organization needs something defensible, not just something easy.

When a Pre-Post Design Is the Right Tool

There are real situations where a pre-post design is not only acceptable, but smart.

Early-Stage Pilots and Internal Learning

When the goal is learning rather than proving, pre-post can be a great starting point.

Imagine a district piloting a new literacy intervention in a small number of schools. Leaders aren’t ready to scale it. They want to see whether early outcomes are moving in the right direction and whether implementation support needs to change. A pre-post analysis can help answer those questions quickly.

Or consider a nonprofit launching a new mentoring model. The program team wants to know whether participation aligns with improved attendance or fewer behavioral referrals compared to each student’s own baseline. That’s not a final verdict on impact. It’s a practical learning loop that can guide improvement.

In these cases, pre-post works because it’s being used with humility. The results stay close to the people doing the work. The claims remain modest. The purpose is iteration, not persuasion.

Descriptive Monitoring and Accountability

Pre-post can also support descriptive monitoring when the language stays honest. Statements like “Outcomes improved during the period the program was implemented” or “Participants showed gains compared to their baseline” can be accurate. And they’re often useful.

However, they’re also easy to misunderstand if readers assume the program caused the change simply because the timeline matches. This is where disciplined writing matters. If a pre-post analysis is being used, the communication should match what the design can support: describing patterns, not declaring causality.

Situations Where No Reasonable Comparison Exists

Sometimes, you can’t construct a credible comparison group. Small populations. Universal rollouts. Specialized services where “similar non-participants” don’t exist. Unique student needs where comparisons would be misleading or ethically uncomfortable.

In these situations, a pre-post design may be the only feasible option. The key is to treat it as a constrained method, not as definitive evidence. Transparency about limitations is what preserves trust.

Why Pre-Post Designs Break Down in High-Stakes Decisions

When the decision is high-stakes, pre-post designs often break down for one simple reason: Time does not stand still.

Student outcomes change for many reasons that have nothing to do with a single program. In a district setting, multiple initiatives are often running at once. Staffing shifts. School leadership changes. Attendance patterns change. Curriculum updates roll out. Testing windows move. Community conditions change. Student enrollment shifts.

Even without any program at all, you would expect many outcomes to move over time.

A pre-post design has no built-in way to separate program impact from everything else happening during the same period. If outcomes rise, the program gets credit even if the same rise would have happened anyway. If outcomes fall, the program gets blamed even if external forces drove the decline.

This is exactly why internal validity threats matter in evaluation design, especially threats like maturation, history, and regression to the mean.

If you’ve ever watched a “before and after” result get debated in a leadership meeting, you’ve seen this play out in real time. Someone will ask, “What else changed that year?” Another person will point out that a district-wide initiative launched at the same time. A third person will note that the schools that opted into the program were already improving. Suddenly, the clean pre-post story isn’t clean anymore. Unfortunately, it’s the predictable limitation of the design.

Why “After” Feels Like “Because”

Pre-post designs are especially persuasive because they align with how humans naturally think.

We look for cause-and-effect. If a program begins and later outcomes change, our brains want to connect the two. The narrative feels responsible. It feels data-driven. It feels like we’re doing the right thing by measuring results.

This is where good evaluation protects good intentions. A timeline is not a counterfactual. A change is not proof of cause. And the more high-stakes the decision, the more dangerous it is to treat a timeline as evidence of impact.

This is also why major education evidence standards bodies do not treat single-group pre-post designs as sufficient for causal claims.

That position reflects decades of experience seeing how easily confident claims can outpace what the design can support.

If your job is to stand in front of a school board, a superintendent, a procurement committee, or a funder and say “this worked,” you need evidence that can survive reasonable questions. Pre-post alone usually cannot.

How Pre-Post Designs Can Be Strengthened Without Becoming Overwhelming

Here’s the good news: you don’t have to choose between “simple” and “rigorous.” Pre-post designs can be strengthened with a few design moves that keep burden low while dramatically improving defensibility.

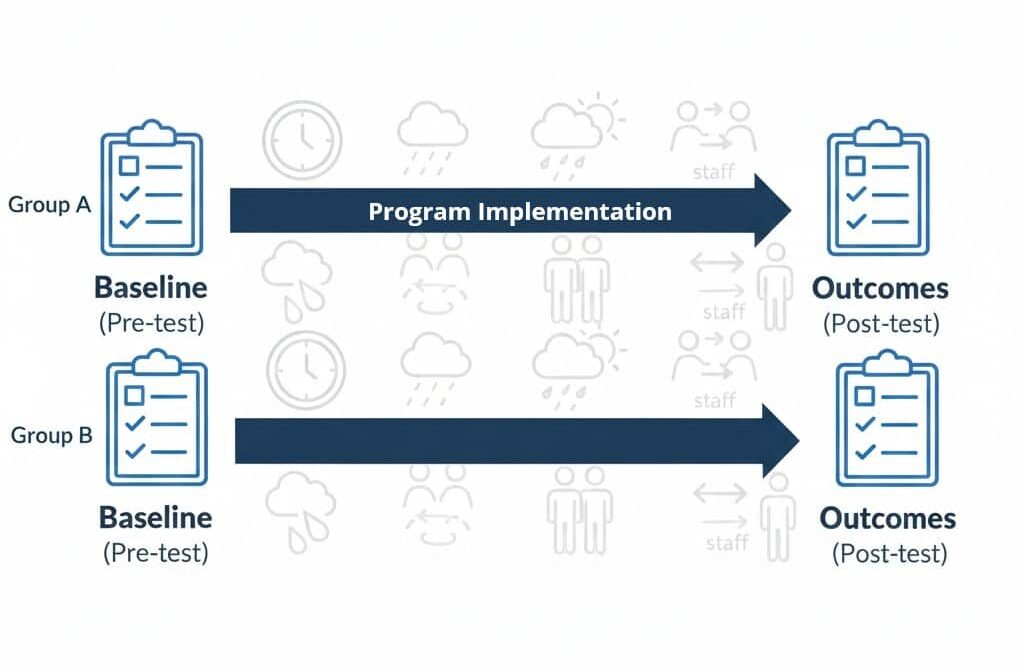

Add a Comparison Group

The single biggest improvement is introducing a group that did not receive the program. Even a modest comparison changes everything.

Now you’re no longer asking, “Did outcomes change?” Instead, you’re asking, “Did outcomes change differently for participants than they did for similar non-participants during the same period?”

That shift brings you into quasi-experimental territory, where designed comparisons are used when random assignment isn’t possible.

The phrase “designed comparison” matters. A comparison group isn’t helpful just because it exists. It has to be credible. It has to represent what likely would have happened to participating students if they had not received the program.

Pay Attention to Baseline Differences

A common failure mode in K–12 evaluation is the “comparison group” that isn’t comparable.

Programs are rarely assigned randomly in real districts. Schools opt in. Teachers choose to participate. Students are selected based on need. High-engagement users differ from low-engagement users in predictable ways. If those differences exist before the program starts, post-program differences may simply reflect starting gaps.

This is why baseline equivalence matters. If the groups were already meaningfully different, you can’t interpret post-program gaps as impact. You’re just observing the continuation of pre-existing differences.

Move From Simple Change to Relative Change

Difference-in-differences logic focuses on relative movement, not just absolute outcomes.

The question becomes: did the treatment group improve more (or decline less) than the comparison group over the same period?

This logic helps address the real-world reality that both groups experience the same broader context: policy changes, staffing shifts, schedule disruptions, and district initiatives. By comparing change over time across both groups, you reduce the risk of crediting the program for changes driven by the environment.

This is one of the reasons quasi-experimental methods are often the workhorse of practical education program evaluation. They don’t require perfect conditions. They require careful design.

Why Some Standards Push Beyond Pre-Post

It helps to say this plainly: if your goal is to claim “impact,” you need more than “before and after.”

Evidence review standards emphasize this because the risks of misattribution are not theoretical. They show up as wasted dollars, misdirected scaling decisions, and programs being cut or expanded for the wrong reasons.

What Works Clearinghouse® training materials are blunt about what does and does not meet group design standards. The goal is to protect decision-makers from overclaiming and to encourage designs that match the question being asked.

Why Decision-Makers Rarely Regret Moving Beyond Pre-Post

In practice, leaders don’t regret stronger evidence because it complicates the story. They regret weak evidence when it collapses in public.

District leaders are accountable to boards, families, and communities. EdTech leaders are accountable to procurement teams and customers who increasingly ask for evidence. Nonprofit leaders are accountable to funders who want outcomes, not anecdotes.

In that environment, evidence has to do more than sound reasonable. It has to be defensible.

That doesn’t mean every evaluation needs to be a randomized controlled trial. It means the design should be strong enough to answer the question being asked, with clear limits and transparent assumptions.

Pre-post designs can still play a role, but they work best as an early signal or descriptive tool, not as the final justification for major decisions.

How MomentMN Snapshot Reports Address the Limits of Pre-Post Designs

MomentMN Snapshot Reports were built for the exact gap districts and partners keep running into: the need for evidence that is rigorous enough to inform decisions, but practical enough to fit real timelines and real data environments.

Snapshot Reports retain what makes pre-post designs attractive:

- They leverage existing district data

- They minimize burden on staff

- They focus on outcomes leaders already care about

But they address the core limitation that makes pre-post fragile: the absence of a credible counterfactual.

By using a quasi-experimental, between-groups pre- and post-test design with multivariate matching via propensity scores, MomentMN Snapshot Reports estimate what would have happened to similar students who did not receive the intervention.

That’s the difference between “scores went up” and “scores went up more than they would have without the program. It’s the kind of evidence that can be explained clearly, defended honestly, and used to make decisions without pretending the world stood still.

Choosing the Right Tool for the Question You’re Being Asked

A simple way to choose the right design is to listen carefully to the question hiding underneath the request.

If the question is, “Did outcomes change during implementation?”, then a pre-post design may be enough.

If the question is, “Did this program improve outcomes enough to justify continued investment?”, then a stronger design is required.

When districts, nonprofits, and EdTech companies are making choices that affect thousands of students and significant budgets, the evidence should be built to carry that weight.